Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters

After the Civil War, George Pullman’s company became the largest employer of African Americans in the country. But his refusal to pay his porters a fair wage created a different legacy: the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, the first African American-led labor organization to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor.

After the Civil War, George Pullman’s company became the largest employer of African Americans in the country. But his refusal to pay his porters a fair wage created a different legacy: the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, the first African American-led labor organization to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor.

After the Civil War, George Pullman’s (designer and manufacturer of the Pullman sleeping car) company became the largest employer of African Americans in the country. But his greed and refusal to pay his porters a fair wage created a different legacy: the creation of the first labor organization led by African Americans to receive a charter from the American Federation of Labor. They were known as the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, and they made their first moves in the fight for labor equality right here in Harlem.

The Beginning

In 1867, George Pullman started hiring freed slaves to work in his sleeping cars – passenger train cars that were considered the height of luxury and comfort when it came to railroad travel. Because these workers were desperate for a job, Pullman exploited their labor by demanding long hours – something like 73-hour weeks at 27.8 cents per hour while manufacturing jobs were currently averaging 37-hour weeks at 54.8 cents per hour, for example – and went unpaid for “preparatory hours” when they were setting up or cleaning the sleeping cars in preparation for their guests. The porters also had to pay for their own food, lodging, and uniforms while the men were told they would not be eligible for the promotions to “conductor” status that their white counterparts received.

Because of this mistreatment and frustration by the inactions of the company organization that was supposed to handle employee representation matters, the porters started trying to organize a union to aid in the fight for fairer work conditions.

The First Meeting in Harlem and the Official Organization

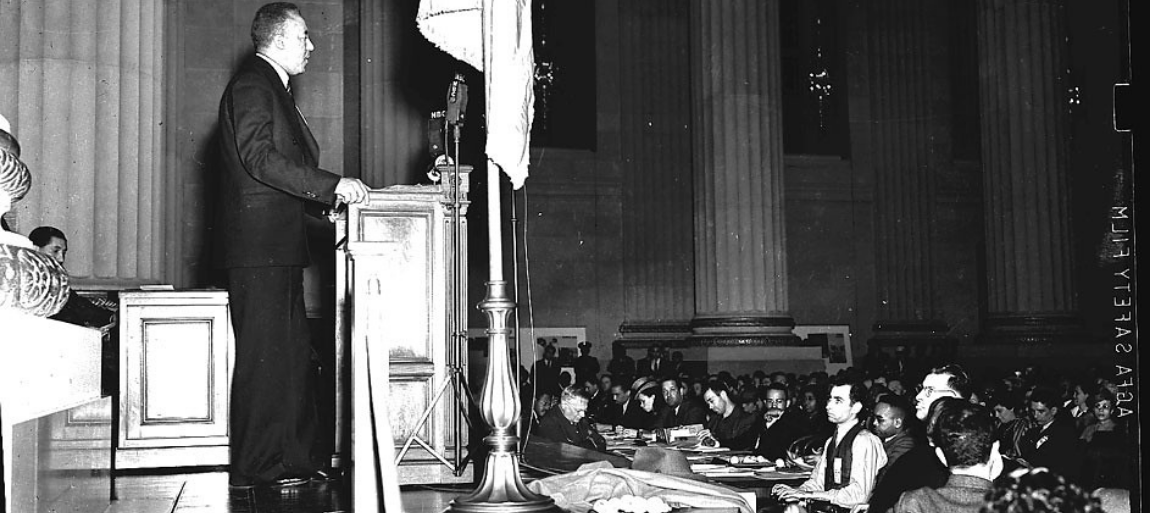

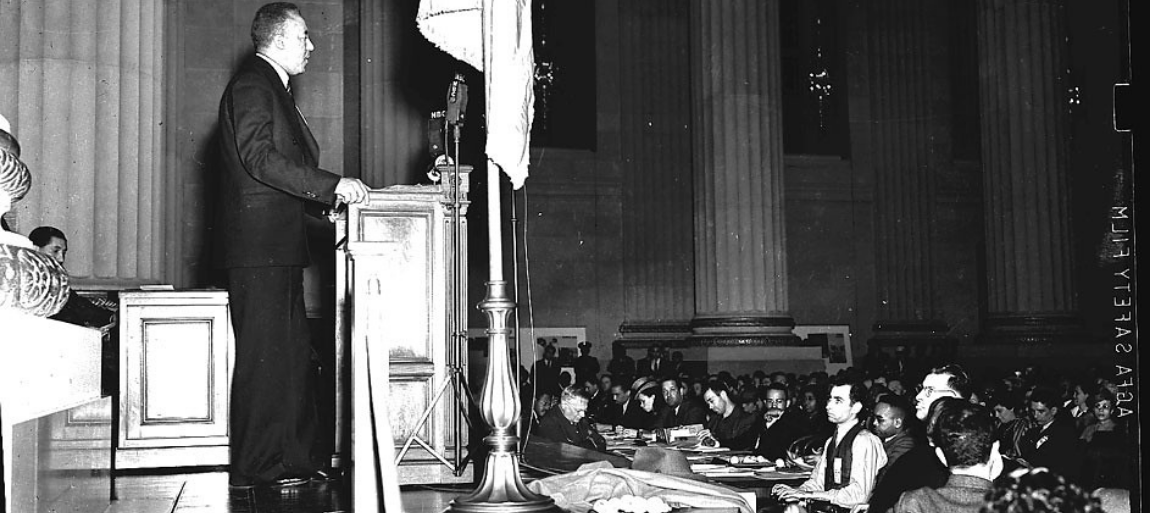

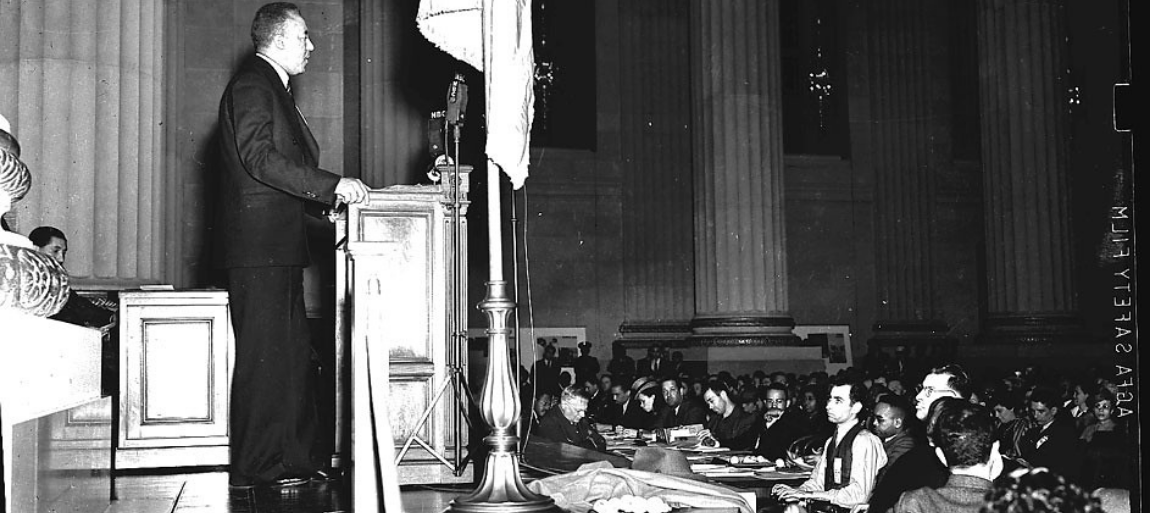

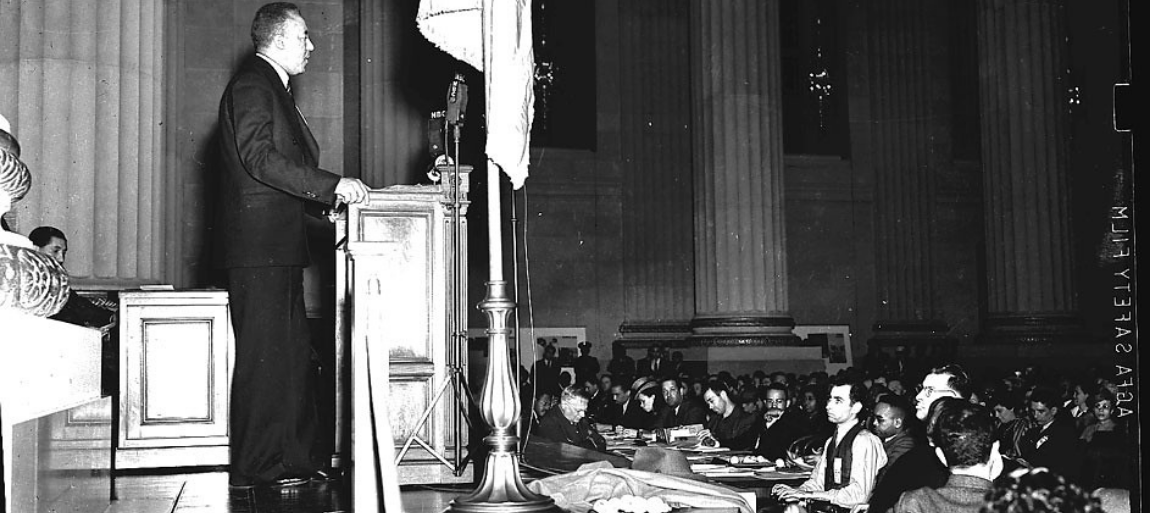

On August 25, 1925, 500 Pullman porters met in secret at the Elks Lodge on 129th Street in Harlem to organize the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP).

This meeting began a 12-year-long journey to get the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters to actually be recognized by the American Federation of Labor. BSCP co-founder and first vice president Milton Price Webster said of the struggle to get a Black labor union accredited by a white governing body: “Any time we have an American institution composed of white people there is prejudice in it…In America, if we should stay out of everything that’s prejudiced we wouldn’t be in anything.”

That 12-year battle was initially drawn out by the Pullman Company, which used its contacts in Black communities all over the country to pressure, persuade, and even physically attack individuals who were thinking of joining.

For many years, especially during the Great Depression, the Brotherhood looked like it would never be able to accomplish its goals, but a dedicated few – led by Webster, A. Phillip Randolph, and the other initial organizers, who were fiercely protective of their dream: a commitment to “the imperative that the Black worker be organized to improve the working conditions, workers’ rights, and the lives of Black workers, their families, and their communities.”

The BSCP Legacy

The Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters finally gained a charter from the American Federation of Labor in 1935, and the union expanded its divisions across the country and even into Canada. By 1945, BSCP and the work done through it had affected positive wage reform, working standards, and member expansion. A. Phillip Randolph’s effectiveness in his roles and speaking engagements in relation to the BSCP gave him more power to affect change in the AFL and even go on to lead the National Negro Congress, an organization that helped paved the way for the modern civil rights movement in the 1940s and onward. In 1947, he again leveraged his powerful position as a leader in the fight for racial equality to demand President Harry S. Truman end racial segregation in the military – which he achieved.

Many BSCP founders and members would go on to lead the way for Black initiatives and organizations for decades to come.

If you want to learn more about the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, who quietly got their start in the heart of Harlem, you can check out the documentary Miles of Smiles: Years of Struggle – you can watch a preview here and the whole film is available to rent at this link.

The Power of the Black Community

Once A. Phillip Randolph had established himself, he was unstoppable. He had dreams he turned into goals, which it turned into plans. Are you ready to make some plans to take your established business to the next level? HarlemAmerica Digital Network is the perfect home for your podcast or TV show.

Interested? Check out our website to learn more about our small business membership packages.